Executive Summary

This primer points out key targets in Algeria’s climate strategies and analyzes the main takeaways from our database on climate governance, outlining how Algeria’s national institutional, regulatory, and legal frameworks interact with its climate mitigation and adaptation goals. The analysis evaluates institutional tools on two axes: sound climate policies and good governance practices. It assesses the country’s climate policies in terms of how well they achieve goals related to establishing long-term, short-term, or foundational targets; addressing risk and vulnerabilities; mitigation; or adaptation. The governance metrics used to analyze the quality of Algeria’s climate framework are based on the following criteria: actionable goals, authority and management powers, transparency, accountability, representation, human capacity, financial capacity, and oversight capacity. By expanding on the database, the primer offers an overview of Algeria’s climate governance, identifies areas of progress as well as institutional gaps, and suggests potential policy actions and plans.

Overview: Algeria’s Political and Economic Conditions

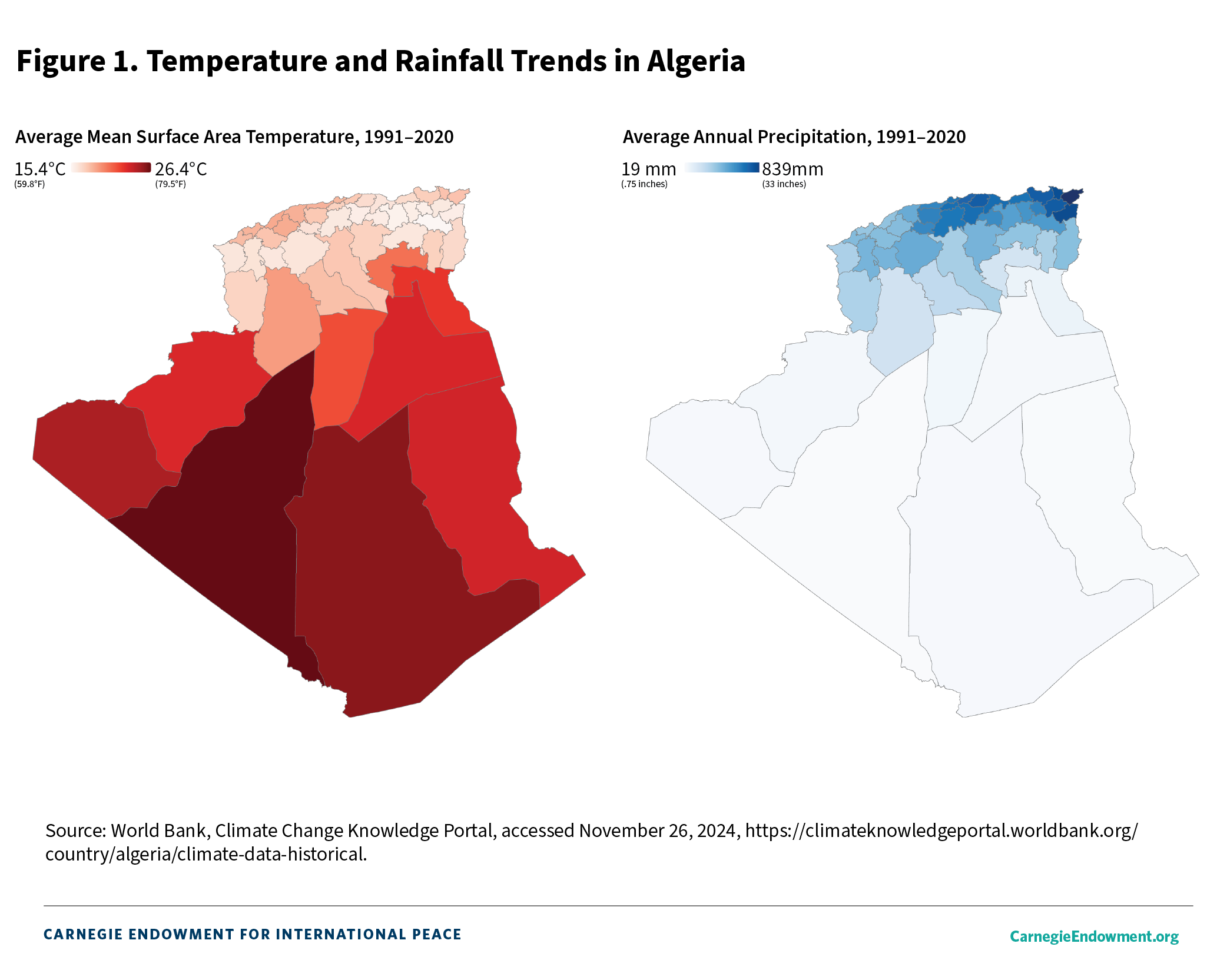

Algeria spans over 2 million square kilometers and straddles two distinct climates, mirroring other North African countries’ environmental conditions and corresponding vulnerabilities. Although the country’s northern coast has a Mediterranean climate, much of the rest of the country has a desert climate; the only part of Algeria that receives more than 400 millimeters of annual rainfall is a narrow strip within 150 kilometers of the coast. Algeria is thus faced with climate vulnerabilities common among arid and semi-arid nations, such as desertification, water scarcity, and extreme heat, all of which are further exacerbated by the increasing pressures of climate change. Algeria’s vulnerability to climate change extends beyond environmental impacts and includes the national economy. For example, the country’s rapidly growing population—which quadrupled between 1960 and 2020—has catapulted demands for drinking, agricultural, and industrial water, which have not been wholly met and are further straining natural resources. Faced with these challenges, the Algerian government has deployed a climate strategy that advances mitigation and adaptation policies responsive to its risk and vulnerability profile. Algeria’s social, political, and economic conditions are central to understanding the context of the country’s climate governance and evaluating its efficacy.

Algeria’s social landscape consists of a diverse population that includes Arabs, who make up an ethnic majority, and Berbers, an ethnic minority in the Kabylie and Sahara regions. Additionally, the country grapples with high unemployment rates, particularly among youth, and widespread poverty in certain areas, including the Kabylie region. While the education system has made strides in the past two decades, lack of sufficient quality and access have led to a growing brain drain as educated young people seek opportunities abroad. Social unrest—fueled by demands for political reform, economic opportunities, and better living conditions—has become more common, particularly following the Hirak movement that began in 2019 and called for systemic change and accountability.

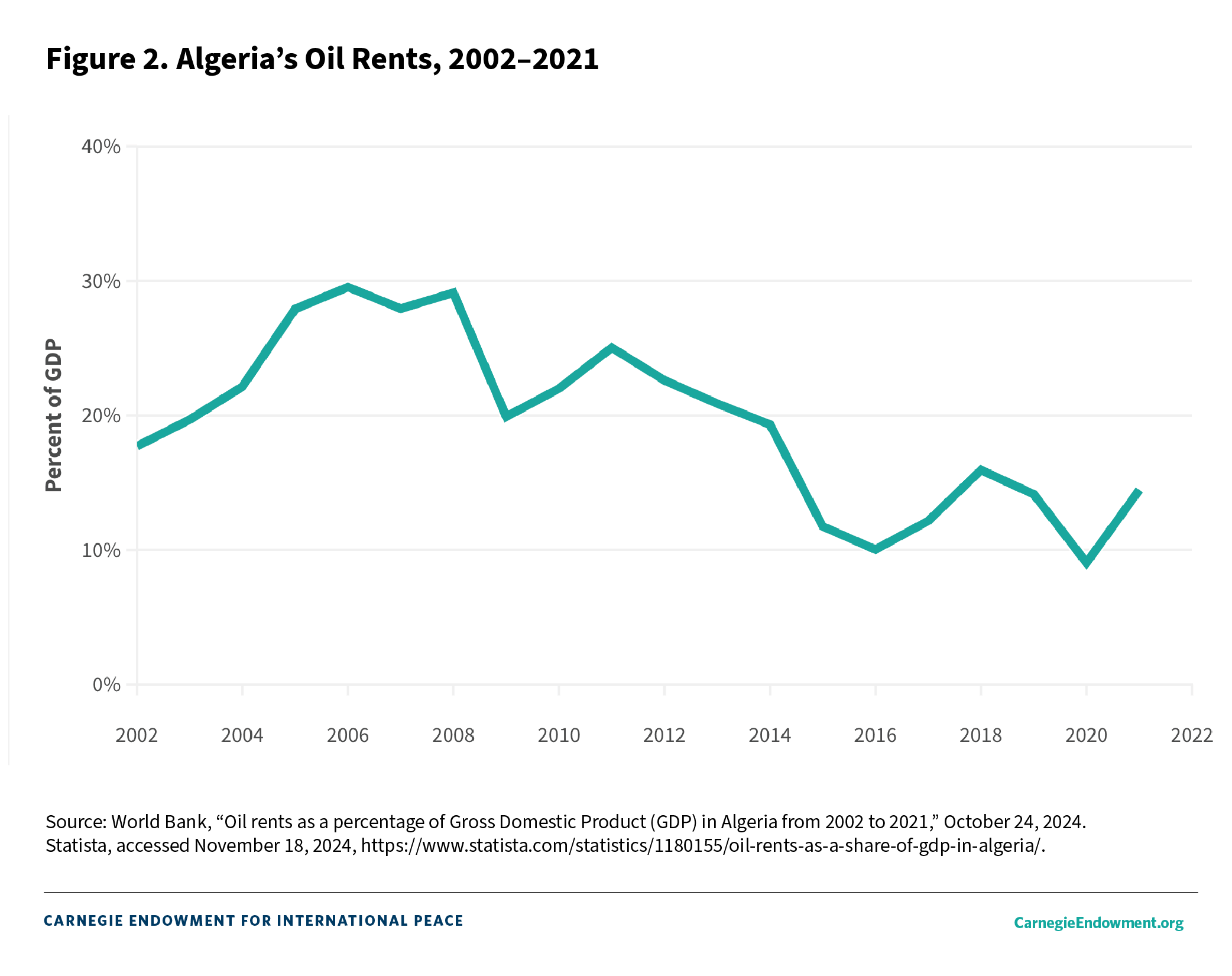

Economically, Algeria is heavily reliant on hydrocarbons, with oil and gas accounting for a substantial portion of government revenues and export earnings. This dependence makes the economy vulnerable to fluctuations in global oil prices. Although efforts have been made to diversify the economy, challenges such as bureaucratic inefficiency, a lack of private sector development, and infrastructure deficits persist. Politically, Algeria has a complex system characterized by a strong presidency and significant military influence. While the government has taken steps to implement reforms, political discontent remains high, with calls for greater transparency and democratic governance continuing to resonate among the populace. President Abdelmadjid Tebboune was elected for a second term in 2024 and has previously issued a presidential decree attempting to further centralize presidential power. A potential future of inclusive climate governance in Algeria will, however, hinge on decentralization within and between ministries, municipalities, and local nonprofit organizations.

Confronting Climate Challenges: Algeria’s Adaptation and Mitigation Strategies Amid Growing Vulnerabilities

Algeria’s diverse climatic zones face increasing vulnerabilities due to climate change. The Algerian government has implemented climate strategies aimed at both mitigation and adaptation, guided by its Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) and National Climate Plan (PNC), which outline specific goals for climate-sensitive sectors. While Algeria has seen an increase in climate investments, budget allocations for renewable energy remain minimal. Overall, Algeria’s revised climate governance strategy balances between mitigating greenhouse gas emissions, adapting to the impacts of climate change, and addressing climate-related vulnerabilities. As such, the country has taken steps to enhance its institutional mandates by expanding its regulatory and human capacities, stakeholder engagement and transparency in decisionmaking. However, there remains a lack of clarity in identifying clear short-term and long-term targets within Algeria’s climate governance framework, in addition to a shortage of policies that are sector-specific.

While Algeria’s climate efforts precede the UN’s Paris Agreement, the country’s INDC and PNC largely frame its current strategies to advance adaptation and mitigation. In terms of adaptation, the Algerian state has put forward three broad goals: reinforce the resilience of ecosystems to minimize natural catastrophes linked to climate change; combat land erosion and desertification; and integrate climate change strategies in sectoral work, particularly agriculture, hydraulics, human health, and transportation. Notably, relevant state and non-state institutions—namely the Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy and the UN Development Programme—have identified several governance steps necessary to best advance these plans. They include:

- improving institutional framework, cross-sectoral integration, local capacity-building, and coordination of local-national priorities;

- creating a centralized information system and evidenced-based measures; and

- engaging and mobilizing the private sector and its capital.

The adaptation priorities delineated in Algeria’s INDC focus on four main sectors. First, energy: the country has pledged that by 2030 it will produce 27 percent of its electricity using renewables, disseminate the use of efficient lighting and thermal insulation, and increase the use of liquefied petroleum gas and natural gas in its hydrocarbon consumption. It also targets the forestry sector by driving reforestation efforts as a carbon capture solution, and the waste management sector through the implementation of initiatives decreasing methane emissions and pollution. Finally, the INDC commits to a national education plan that disseminates accurate information and communicates the stakes of the climate crisis. Algeria’s PNC translates these plans into terms of greenhouse gas emissions by setting a goal of reaching 7 percent emissions reduction through national means, or 22 percent with the help of international support, by 2030.

Given the Algerian government’s priorities as outlined in its INDC, this database focuses on the following seven ministries: the Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy; the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development; the Ministry of Water Resources and Environment; the Ministry of Public Works and Transport; the Ministry of Interior, Local Authorities, and Regional Planning; the Ministry of Finance; and the Ministry of Commerce. While education is a key part of Algeria’s climate strategy, it is outside the scope of this project because it is neither a high-emitting sector nor directly related to environmental or ecosystem management. Importantly, the Ministries of Energy, Water Resources and Environment, and Public Works and Transport do not have their laws published under their website domains and thus were not included in the below analysis. This underlines the country’s need for greater institutional capacity; publicly available regulations are necessary for coordinating effective strategies across sectors and levels of government. This lack of transparency also creates obstacles for non-state actors—including civil society groups, the private sector, and development organizations—seeking to contribute to climate efforts.

Budgeting for Change: Assessing Algeria’s Financial Commitment to Building Climate Resilience

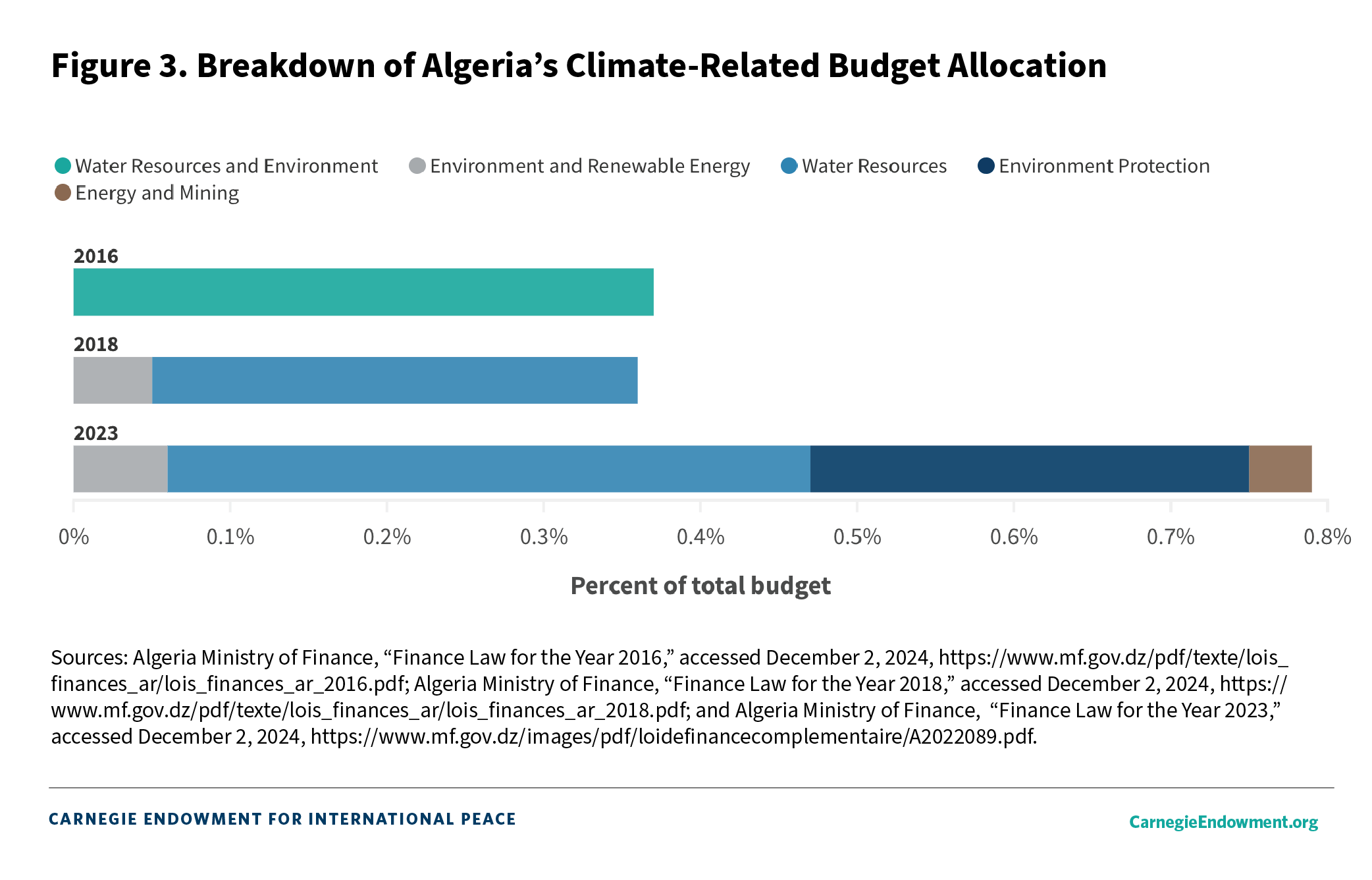

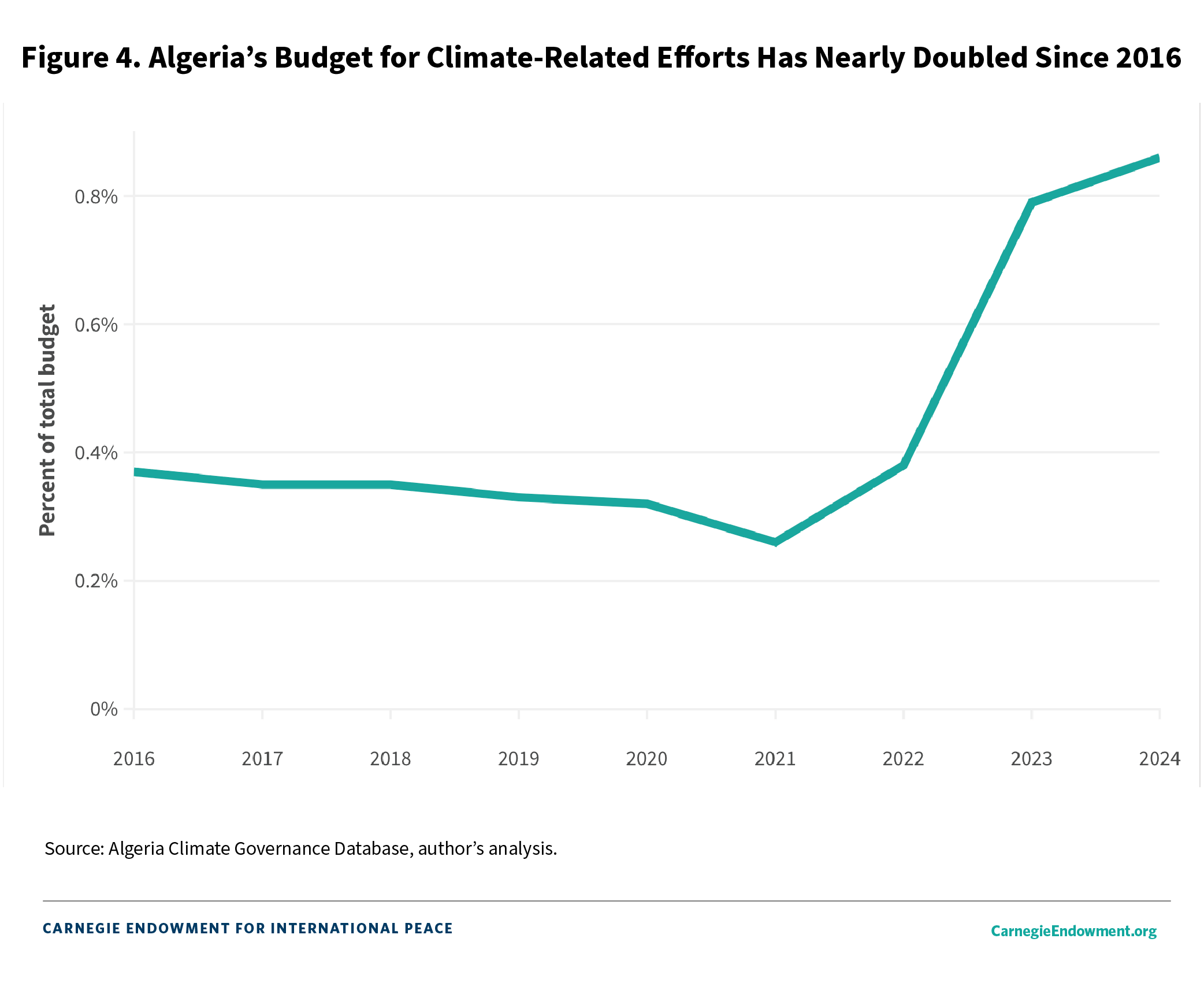

The budgetary component of this analysis validates Algeria’s increasing commitment to responding to the consequences of climate change. However, the government’s financial allotment to renewable energies remains insufficient to build the capacity necessary for its national goals. Indeed, Algeria has increased its budgetary allocation to climate efforts and established more budget allocations relevant to its national climate strategies from 2016 to 2024. While the Algerian government only had one climate-responsive budget line item in 2016—“water resources and environment”—it had incorporated four by 2023: “renewable energy” as part of the Energy and Mines budget; “purification and protection of the natural environment” and “mobilizing resources for water and water security” as part of the Irrigation budget; and the Environment and Renewable Energy budget.

Since 2016, Algeria has more than doubled its budgetary allocation to climate-related programs, which grew from 0.37 percent of the country’s total budget to 0.86 percent in 2024. Given the cross-sectoral impact of the climate crisis and the country’s vulnerability levels, this allocation remains relatively small. For context, the Energy and Mines budget, excluding the “renewable energy” program, received 1.12 percent of the country’s total budget for 2024. Water security consistently receives the largest proportion of the budget committed to climate-related work, which reflects the country’s vulnerability profile as well as its national strategies.

Renewable energy efforts, however, receive a very low percentage of the total budget. In 2024 and 2023, for example, only 0.09 percent and 0.1 percent respectively were dedicated to renewable energy programming. The minimal financial capacity distributed to clean energy deployment could potentially undermine Algeria’s INDC mitigation commitment to produce 27 percent of national electricity through renewable energy. As of 2022, only 0.7 percent of the country’s electricity generation came from clean energy sources. The Algerian economy is also highly reliant on fossil fuels, which accounted for 19 percent of the country’s GDP, 93 percent of its product exports, and 38 percent of its budget revenue between 2016 and 2021. There is thus room for improvement in translating national commitments to a cleaner energy mix within budgetary and institutional capacity. This is especially salient because demand for fossil fuel is expected to decrease as global energy trade policies increasingly incentivize a move toward clean energy.

Database Analysis: Evaluating Algeria’s Climate Governance Framework

In an effort to better integrate environmental considerations into its development agenda, Algeria has taken measures to revise its governance framework. A 2021 constitutional revision renamed Algeria’s Economic and Social Council, making it instead the National Economic, Social, and Environmental Council (CNESE). This change reflects Algeria’s efforts to better align its institutions with Law No. 10-03, which establishes environmental protections as part of the country’s sustainable development plans. The CNESE acts as an advisor to the Algerian government with the goal of strengthening socioeconomic and environmental development plans, legislative policies, regulations. However, the government does not necessarily publish any information on the specific stakeholders involved, the processes for consultation among stakeholders, or the output of the CNESE’s suggestions, which makes it difficult to assess the efficacy of the CNESE in supervising climate strategies.

Overall, Algeria’s institutional tools—ministerial laws, decrees, and decisions—evaluated in our database outline clear goals, policy design, execution processes, and stakeholder involvement. These processes and standards specifically address political appointments, identifying climate-threatened areas, conducting environmental impact and assessment studies, mitigating harmful practices in high-emitting sectors, financing climate strategies, and creating inclusive environmental policies. Strong oversight mechanisms have been exercised through the regulatory actions of the Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy; the Ministry of Interior, Local Authorities, and Regional Planning; the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, the Ministry of Commerce; the Ministry of Public Works and Transport; and the Ministry of National Defense.

It is important to underscore, however, that only a little over half of the policies issued by these bodies in total explicitly connect their actions to mitigating or adapting to climate risks and the social, economic, and infrastructural vulnerabilities caused by climate hazards. Algeria’s frameworks on mitigation and on waste and agriculture management, including its national funds for incentivizing sustainable agriculture (Decision No. 146) and energy production (Law 99-09) are examples of policies that do make this connection explicit. Adaptive capacity could greatly benefit from a climate risk and vulnerability nexus approach, which would mean approaching environmental hazards as threats to resources, health, and economic and social security. Similarly, financial assistance conditioned on measurable reductions in climate risks and vulnerabilities is essential for achieving sufficient adaptive capacity.

Algeria’s climate governance framework does well in splitting resources equally between climate mitigation and adaptation problems. Out of the thirty-one institutional tools evaluated in the database, eleven focus on mitigation and thirteen on adaptation. Efforts toward structural resilience can be seen in Algeria’s National Plan for Environmental Activity and Sustainable Development, whose mandates are specified in Executive Decree 207-15. This plan prioritizes preventative and disaster-recovery measures based on the extent of economic loss imposed on communities most acutely exposed to environmental hazards. Cross-sectoral consultations are a key element of the plan’s approach to addressing the broad social and economic ripple effects of climate change, which of course also include human health and security. Such cross-sectoral politics and initiatives bolster Algeria’s governance capacity and abilities to advance its climate strategies.

It is worth noting that Algeria’s frameworks for coastal management systems in particular embrace cross-sectoral and interministerial coordination between the environment, renewable energy, transportation, and defense sectors. Algeria’s permit assignment and reporting system and expansion of green infrastructure built to preserve public health and safety are concrete examples of the country’s commitment to oversight and transparency through coordination between stakeholders and across various levels of government. The creation of new organizational bodies to manage policy implementation and streamline responsibilities is a vital determinant of effective oversight capacity. Algeria has already created some such bodies, like the committee to study the National Plan for Environmental Activity and Sustainable Development, the National Agency for the Valuation of Hydrocarbons Resources (in other words, oil resources), and the National Waste Agency (which monitors environmental violations). Through these new agencies, Algeria has sought to create human capacity by delineating new roles to advance climate goals and to facilitate coordination across sectors and levels of government. As a whole, Algeria has thus successfully developed its governance capacity to effectively carry out the country’s climate strategies.

The majority of Algeria’s institutional tools are designed to promote transparency and accountability. For instance, Executive Decrees 144-07 and 145-07 require facilities and development projects that create environmental or health risks or that deal with high levels of toxic materials, such as air and noise pollution and water contamination, to obtain permits from the appropriate authorities, conduct environmental risk assessment studies, or notify authorities of their proposed activities. However, there is room for improvement in creating systems to ensure compliance or redress issues; for some of their requirements, Executive Decrees 144-07 and 145-07 do not detail monitoring procedures to guarantee compliance. Shortcomings in enforcing accountability within Algeria’s climate governance strategy are also visible in the frameworks administering development projects in Algeria’s coastal sector intended to bolster environmental protections, such as Executive Decrees 424-06 and 114-09.

Additionally, while Algeria boasts a climate governance structure that aims to satisfy wide-ranging interests, from small private agricultural businesses to national energy companies, it still lacks regulatory frameworks targeted toward specific sectors. The bulk of its institutional tools (twenty-five of the thirty-one tools evaluated in the database) focus on national-level mitigation and adaptation practices. Notably, this analysis does not include regulations and other governance tools from key high-emissions sectors (namely transportation and energy, because of a lack of data availability). Without this information, it is unclear whether Algeria is sufficiently targeting the industries that will need to decarbonize if the country is to achieve its 2030 goals. Per the data available, it appears that much of the climate strategy is deployed within the Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy’s purview, potentially siloing climate efforts instead of creating a comprehensive strategy that targets all segments of the country’s governance and economy.

Finally, most of the tools evaluated in the database advance foundational goals; in other words, they call for the implementation of evergreen policies that set an important basis for further climate initiatives. However, they do not set specific targets that concretely advance the country’s climate strategy within the short or long term. The Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy’s Executive Decree 19-09, for example, sets processes by which residents can organize their waste collection activities led by an “association.” While the process for waste collection is meant to be implemented in the short term, its application as outlined in the decree is intended to continue indefinitely. This decree sets a vital starting point for future effective waste policies, but does not target a tangible result—such as a specific volume of adequately sorted waste—within a set time period.

Laws that advance foundational goals, like Executive Decree 19-09 or the previously discussed Executive Decrees 144-07 and 145-07, are vital in creating the structure necessary for a country’s climate strategy. Many of them also seek to enable the Algerian government to create centralized, standardized, and evidence-based measures. However, setting short- and long-term targets focused on outcomes as opposed to implementation processes is equally crucial. Out of the thirty-one policies in the database, only Executive Decree 240-05 (which regards appointing representatives for the Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy) identifies a long-term target (achieving specific goals between 2050 and 2060). Further, for most budgetary laws and national climate strategies directed toward mitigation targets, Algeria has only identified short-term or immediate targets (goals to be achieved by 2030). Establishing climate objectives tied to designated timelines is another important next step for incentivizing accountability and enhancing Algeria’s organizational capacities in managing climate issues.

Conclusion

Continued temperature increases in Algeria are forecasted to bring about spikes in malnutrition, food production loss, and infectious and non-communicable diseases. Algeria’s water resources, of which the agricultural sector consumes around 64 percent, will be increasingly strained by growing demands for water and food coupled with diminishing water availability caused by droughts, low precipitation, and over-extraction. To achieve water security—which is vital for fueling consumption, production, food security, and transportation—it is essential to bolster technological and infrastructural capacities. Climate change is thus a threat multiplier that must be met with timely, concerted, and inclusive governance plans.

To do so and to satisfy both mitigation and adaptation goals, firstly, Algeria must apply equal budgetary allocations toward water security (which has long been a substantial recipient of funding) and the renewable energy sector. Further, to establish long-term adaptive capacity, Algeria’s ministerial laws, decrees, and decisions will need to adopt a climate risk and vulnerability nexus approach that clearly identifies and issues protections for not only environmental harms but also socioeconomic and health vulnerabilities. Additionally, Algeria’s effective oversight capacities must be strengthened with more stringent enforcement requirements to guarantee accountability. Part of this effort would include linking climate objectives (beyond mitigation targets) to designated short-term and long-term timelines. Lastly, while Algeria has remarkably advanced its foundational climate goals at the national level, these goals also need to be more strategically structured and streamlined across levels of government and sectors, moving beyond the Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy as the primary overseer of climate strategies.