On July 30, 2025, the United States announced 25 percent tariffs on Indian goods, noting India’s purchase of oil and arms from Russia. While diplomatic tensions simmered on the trade front, a cosmic calm prevailed at the Sriharikota launch range. Officials from NASA and ISRO were preparing to launch an engineering marvel into space—the NASA-ISRO Synthetic Aperture Radar (NISAR), marking a significant milestone in the India-U.S. bilateral partnership.

Space cooperation has often moved forward in the past despite broader geopolitical tensions. The Apollo-Soyuz handshake took place at the peak of the Cold War; the International Space Station, a multilateral space program that involved Russia and U.S.-led allies, was launched a few years after the Cold War ended. Despite geopolitical rivalries, cooperation in space endured.

Strategic partners like the U.S. and India have had their fair share of highs and lows in space cooperation. After the U.S. supported India’s first sounding rocket launch in 1963, the space relationship between the two countries entered a hiatus until the late 1990s, owing to the U.S.’ dual-use concerns on India’s rising space program. Reinvigorated by the Next Steps in Strategic Partnership initiative in 2004 and the creation of a Joint Working Group on Civil Space Cooperation in 2005, bilateral space collaboration flourished and scientific breakthroughs followed. The Chandrayaan-1, which hosted NASA’s Moon Mineralogy Mapper, detected water molecules on the moon for the first time.

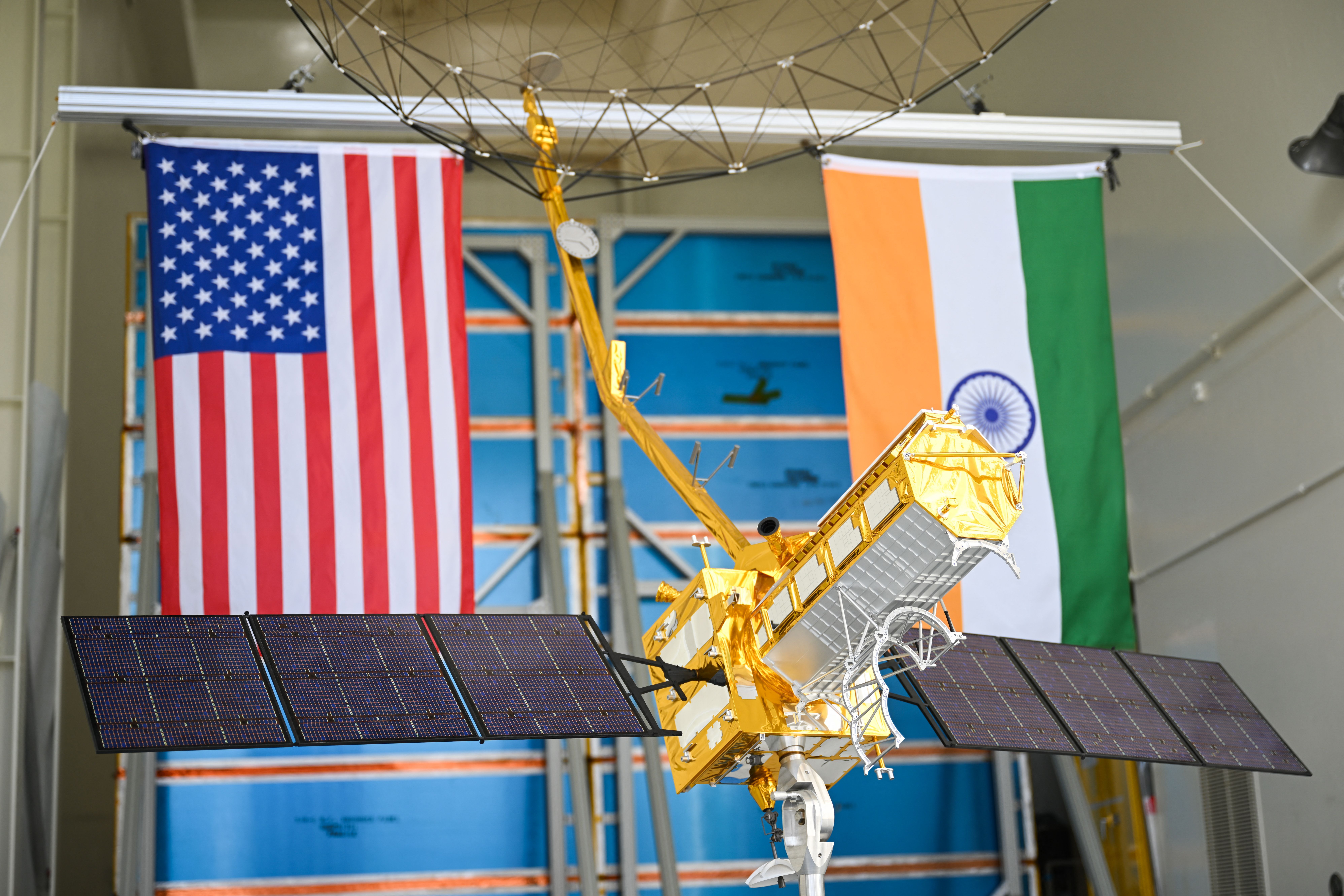

The NISAR satellite’s launch is not the usual tech transfer story involving defense primes and public sector undertakings, but, as remarked, “a 50-50 effort,” indicating an acknowledgement of mutual tech prowess. For the first time, both countries equally co-developed a satellite with the most advanced imaging dual-use radar that can map the slightest changes to the Earth’s surface. While NASA developed the long-range L-band radar system, ISRO developed the short-range S-band radar, solar arrays, satellite bus, and launch. The satellite will orbit the Earth fourteen times a day to observe ice and land surfaces twice every twelve days, and can see through clouds, even during the night. The data extracted will be publicly available and is expected to help predict, understand, and manage natural disasters and the impact of climate change. The two countries have conducted workshops for their respective ecosystem on leveraging the datasets. Notably, this is a program that is expected to last for several decades, beyond administrative changes.

The history of the NISAR satellite also carries a note of geopolitical irony. In 1992, then-senator Joe Biden played an instrumental role in stalling the cryogenic engine deal, an important component for the Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle (GSLV) series of heavy-lift rockets that ISRO was building at the time. The stall delayed the GSLV program by four years. Biden later became president of the United States and launched the India-U.S. initiative on Critical and Emerging Technologies, or iCET (currently TRUST), with the Indian prime minister in 2023 to deepen strategic space cooperation, among other goals. Thirty-three years after the initial setback, the same GSLV launched NISAR into orbit.

The NISAR satellite was not born in a fortnight. It took eleven long years, four different U.S. administrations, and constant exchange of technical expertise between both countries’ space agencies. Teams spent years at each other’s facilities in high-trust environments. American and Indian scientists and engineers worked together despite challenges posed by time zones and a global pandemic.

In addition to the potentially life-saving data that the NISAR satellite will extract, this journey has created a template for more such collaborative programs, with opportunities to tap into the private space sectors of both countries. Following the mission, officials hinted at another joint space program in the future. Perhaps for now, a joint challenge grant program for private space startups from both countries to build applications using NISAR’s dataset could be beneficial, propelled by INDUS Innovation.

As a scientific program that remained insulated from administration changes and geopolitical turbulence, the NISAR satellite also offers a playbook that can be applied to other areas of technological co-development—AI infrastructure for the Global South, a joint quantum lab, a semiconductor fab, or a biopharma unit to boost supply chain resilience.

Amid looming echoes of a strained India–U.S. relationship, things are looking up for space and tech cooperation, a sign of unwavering scientific and strategic alignment.