This piece is part of a Carnegie series examining the impacts of Trump’s first 100 days in office.

Japan’s perception of its relationship with the United States has been upended in the early days of the new administration. Japan’s security alliance, which places it under the U.S. nuclear and defense umbrella, has been the foundation of its security strategy for decades. Now, it can no longer take the umbrella for granted, as President Donald Trump has pointed to what he perceives as the asymmetric nature of the alliance.

Leading politicians have long brought up the question of whether Washington would really defend Tokyo in the event of a military contingency. But now more than ever, the answer to that question is unpredictable. Japan’s shock over how the U.S. president and vice president treated Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky at the White House in February was deep: Could that have been us?

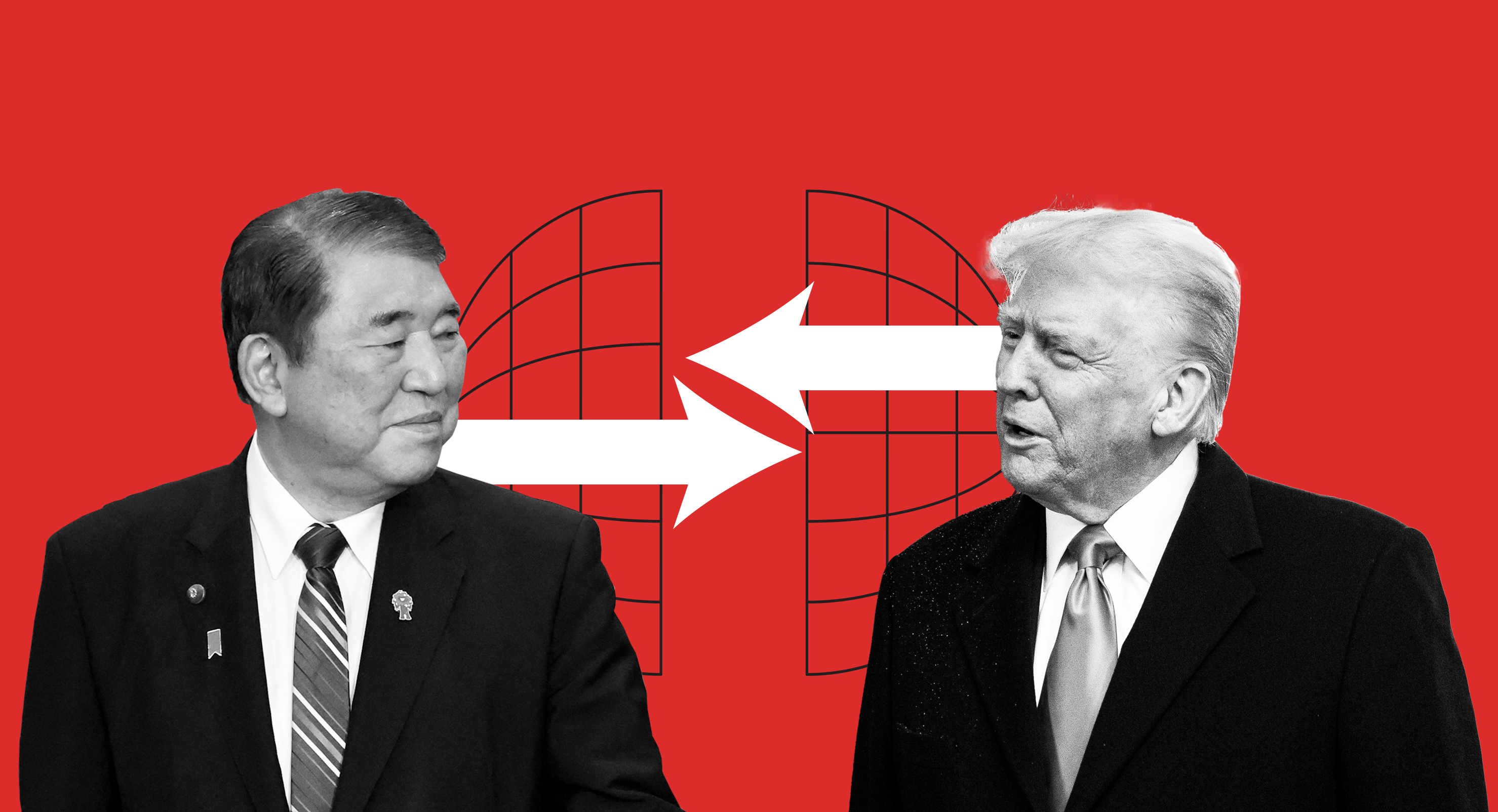

Shortly before the Zelensky meeting, Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba had concluded what many considered a successful summit, in which there seemed no ambiguity about the U.S. commitment to Japan. Yet shortly after, Trump called the alliance “one-sided” in favor of Japan, a claim he repeated in an April Cabinet meeting. In March, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth visited Japan and provided assurances that the alliance was strong. However, his visiting came on the heels of reports from the Pentagon that operational integration efforts between the U.S. military and Japanese Self-Defense Forces would be put on hold. These mixed signals fit the interpretation that the president himself is calling the shots, and the message that the security alliance is very much a card for negotiations is crystal clear.

Trump has also made it clear that U.S.-Japan bilateral security issues and trade and economic discussions are no longer delineated. For years, Tokyo has been maintaining a largely unwavering stance toward the U.S.-Japan security alliance, while identifying China as a military threat and going to great lengths to maintain good trade relations with China. Approximately 21 percent of Japan’s exports are to the United States, and 19 percent are to China. It had hoped that its status as a staunch ally and neighbor to China would enable it to avoid the most damaging U.S. tariffs. Instead, Japan’s fear that perceived friction over trade and economic issues could spill into security issues is exactly what Trump seems to want to convey.

The tariffs have hit major Japanese industries hard, and at many points of their supply chains. NHK estimates that the automobile sector exports roughly $40 billion in goods to the United States. Iron and steel account for $2 billion, construction and mining equipment at $6 billion, scientific and optical equipment at $4 billion, semiconductor manufacturing equipment at $3.5 billion, and food agriculture at $1.6 billion. Given the supply chains that run through other countries, these direct exports from Japan capture only one portion of the value. For example, auto exports also rely on factories and supply chains in Mexico. Many Japanese exports to China are actually then sent to the United States. As part of efforts to decouple supply chains from China, a range of Japanese industries moved parts of their supply chains to countries such as Thailand and Vietnam, which were targeted with tariffs even higher than Japan’s.

America’s reshaping of the world order has accelerated Japan’s move to embed itself in as many bilateral, multilateral, and regional trade and economic frameworks as possible. Overlapping multilateral and regional groups and moves to strengthen bilateral relations with other countries are more important than ever. A free trade agreement is under negotiation with China and South Korea. Japan is even strengthening security cooperation with NATO, including the possibility of opening a NATO office in Japan as a move to cement relations with Europe.

In many ways, Japan reacted to the Trump administration’s moves exactly as the latter intended. In that respect, Tokyo is a model partner. It has already undertaken a major expansion of its defense budget and is braced for U.S. demands to increase its contribution to U.S. defense costs. Ishiba’s visit to the White House revolved around major U.S. projects already underway, such as automobile factories, and promises of new investments, including in the development of a liquified natural gas pipeline in Alaska. Shortly after the administration announced a new round of tariffs on April 2, Japan rushed to the bargaining table by sending Cabinet Minister Ryosei Akazawa to Washington to negotiate more favorable tariff treatment—just as the Trump administration intended.

But Japan is being pushed away by the United States, forcing it to figure out how to get closer again and sparing no effort to do so. The possibility of walking away is not on the table. At the same time, Japan is accelerating its moves to strengthen economic and securities ties with everywhere else. Its relationship with China will remain complicated, as the economic dependence and security concerns pull in opposite directions simultaneously.

Read more from this series: